August 2017

Welcome, Dr. Katie Delph!

Dr. Katie Delph has joined the Equine section at the Kansas State University Veterinary Health Center as a board-certified equine internal medicine specialist. Dr. Delph is originally from Indianapolis, IN where she grew up riding horses in the disciplines of eventing and dressage. Dr. Delph attended Purdue University for both undergraduate studies in Animal Science as well as veterinary school. While she always wanted to be an equine veterinarian, during her fourth year in veterinary school at Purdue, she developed a strong interest in large animal internal medicine. Following veterinary school, Dr. Delph completed an equine internship at the University of Missouri in equine medicine, surgery, and field service. Finally, she completed a three year residency in large animal internal medicine at Kansas State University under the direct mentorship of Dr. Beth Davis and Dr. Laurie Beard. Dr. Delph is excited for the opportunity to continue to practice and teach at the KSU-VHC. She has a strong passion for teaching and greatly enjoys working with students on the equine rotation. Dr. Delph’s research interests have included examining the immunologic responses following strangles vaccination as well as following clinical outbreaks. While she enjoys all aspects of internal medicine, Dr. Delph’s specific interests include neonatology and infectious diseases. Dr. Delph is looking forward to continuing to work with the great clients and referring veterinarians in Kansas and the surrounding areas!

Dr. Katie Delph has joined the Equine section at the Kansas State University Veterinary Health Center as a board-certified equine internal medicine specialist. Dr. Delph is originally from Indianapolis, IN where she grew up riding horses in the disciplines of eventing and dressage. Dr. Delph attended Purdue University for both undergraduate studies in Animal Science as well as veterinary school. While she always wanted to be an equine veterinarian, during her fourth year in veterinary school at Purdue, she developed a strong interest in large animal internal medicine. Following veterinary school, Dr. Delph completed an equine internship at the University of Missouri in equine medicine, surgery, and field service. Finally, she completed a three year residency in large animal internal medicine at Kansas State University under the direct mentorship of Dr. Beth Davis and Dr. Laurie Beard. Dr. Delph is excited for the opportunity to continue to practice and teach at the KSU-VHC. She has a strong passion for teaching and greatly enjoys working with students on the equine rotation. Dr. Delph’s research interests have included examining the immunologic responses following strangles vaccination as well as following clinical outbreaks. While she enjoys all aspects of internal medicine, Dr. Delph’s specific interests include neonatology and infectious diseases. Dr. Delph is looking forward to continuing to work with the great clients and referring veterinarians in Kansas and the surrounding areas!

Update on the West Nile Virus in 2017

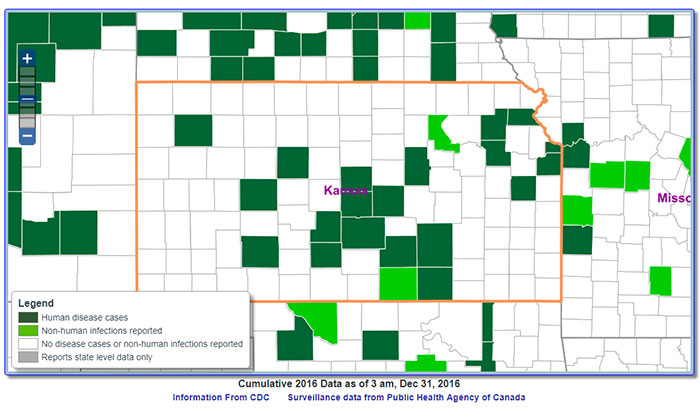

The Equine Disease Communication Center is sending out reports of horses that have neurologic signs (stumbling, unable to bear weight on a limb, unable to rise, and possibly seizures/death) do to West Nile virus (WNV). In this month alone 22 confirmed cases have been reported of horses having WNV disease. This includes a case from Kansas and a case from Missouri.

This information is not novel. The United States has reported human and equine cases every year through the CDC (Centers of Disease Control and Prevention) USGS (United States Geographic Society) website. Below is a map of Kansas with reported cases of WNV in humans and veterinary cases (equine) in 2016.

If an equine patient contract the disease, any neurologic sign could be caused by WNV. Some examples would include:

- Marked lethargy, depression, anorexia

- Stumbling or unable to rise,

- Facial muscle twitching or laxity

- Possibly seizures or even death do to the disease.

In the United States the fatality rate is reported at 33%, horses that become recumbent (unable to rise) have a more guarded prognosis for survival. Treatment in the early stages may help to prevent disease progression that may result in recumbency.

In the United States the fatality rate is reported at 33%, horses that become recumbent (unable to rise) have a more guarded prognosis for survival. Treatment in the early stages may help to prevent disease progression that may result in recumbency.

West Nile Virus has a worldwide distribution, commonly found in the Middle East, Africa and Asia. It was first detected in the United States (U.S.) in 1999 and is now considered endemic in the U.S. The virus maintains a transmission cycle between mosquitoes and wild birds. It is transmitted by mosquitoes that carry the virus to humans and horses, yet it should be noted that horses cannot transmit the disease to humans and humans cannot transmit the disease to horses. The reason for the recent uptick in equine WNV cases is a reflection of mosquito populations at this time of year, particularly in areas of heat and moisture where mosquitoes remain plentiful.

You may ask, “How do we control the WNV disease in our equine patients?” Vaccination protocols have been put into place for horses since the early turn of the century in the U.S. Collectively, it is important to maintain proper immunity against this virus through effective vaccine protocols, limit mosquito feeding by eliminating free standing water wherever practical and to utilize the application of insecticides consistent with label recommendations when possible. Using a multi-pronged approach of enhanced immunity and limited insect exposure / feeding, disease development can be controlled.

Please consult your veterinarian and/or Kansas State University Veterinary Health Center (785-532-5700) if you have questions or concerns about WNV and vaccinations for preventing this disease in your horse.

Heel Bulb Laceration

Dr. Dylan Lutter, DVM, MS, DACVS-LA

It happened in an instant. As she walked out to do the evening chores, Emma saw her old barrel horse, Rocket, put his foot through the fence as he bickered with the crabby broodmare in the next pen. Emma hollered to chase the mare away but before she could get to Rocket he pulled back, catching his foot on the wire and slicing the heel. As Emma cold hosed the leg to clean off the dirt she wondered if she should call the vet. It was only a small cut but it looked deep and Rocket seemed to be more sore than she expected…..

As horse owners, we can all relate to Emma’s story. Maybe it wasn’t the fence and most of the time we never see the wound happen but nearly all of us have experienced a horse with a laceration on its lower limb (distal limb in medical terms).

In Rocket’s case, the wound is a heel bulb laceration. Wounds in this location, no matter how small, have the potential to damage a vital structure, develop a severe infection, and have difficulty healing properly. Within the foot and pastern region there are more than 20 structures that are integral in the normal movement of the horse including joints, large blood vessels, nerves, and a plethora of tendons and ligament not to mention all the structures related to the hoof and its function. Damage to or infection of any combination of these structures could be career or even life threatening if not treated appropriately.

The treatment approach for heel bulb lacerations is similar to other wound but with a couple of important differences. One of these is the high concentration of joints, bursas, and tendon sheaths (aka synovial structures) in the area that could all be involved in the wound. The other is that the horse’s hoof is a dynamic structure which expands and contracts as the horse walks. This creates micro-motion within the wound that delays healing and increases scar tissue production.

|

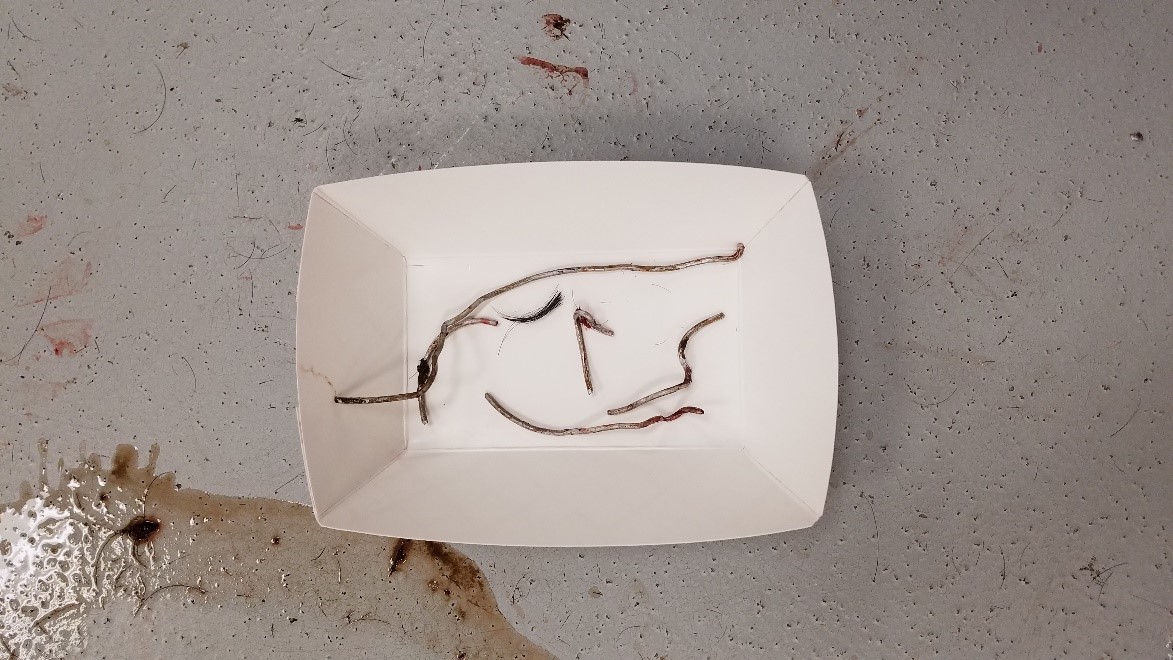

Figure 1. Fresh, clean heel bulb laceration that has been clipped, cleaned, sterilely scrubbed and is ready for wound exploration with closure to follow. |

Figure 2. Chronic, infected heel bulb laceration on presentation that involves the tendon sheath and navicular bursa. |

Figure 2b. Appearance of the same limb three weeks later following arthroscopic surgery, wound debridement, and foot casting at the KSU VHC. The horse returned to his intended use as a rope horse. |

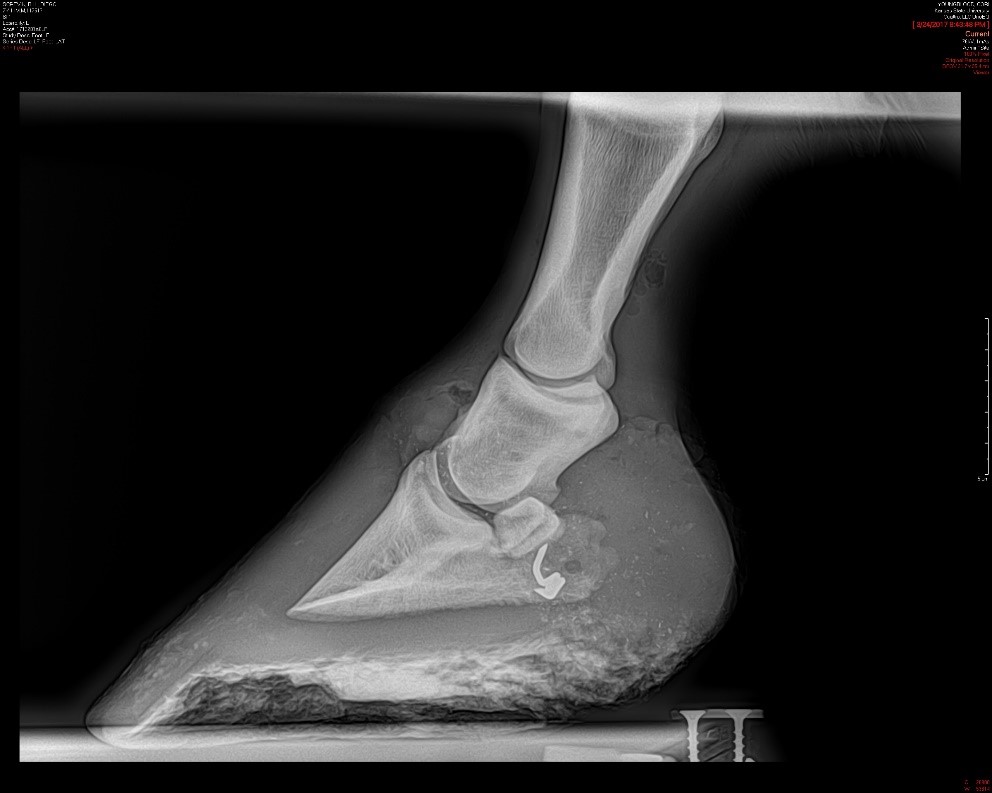

Typically horses that present to the KSU Veterinary Health Center with heel bulb lacerations receive pain medication and sedation from the onset of treatment followed by a nerve block of the affected limb. Commonly, though not always, radiographs are recommended to rule out damage to bony structures or the presence of metallic foreign bodies such as wire.

|

|

|

|

|

Figures 3, 4, 5. Heel bulb and pastern laceration of several days duration which presented to KSU VHC on emergency for severe lameness. The owners did not witness the wound and did not report any wire being present in the pen. Wound exploration found the wire shown in the picture to be buried deep in the tissues. Radiographs after wire removal showed a wire barb was still buried in the wound. |

||

The wound is then clipped of hair, cleaned of debris, and sterilely prepared for exploration. During wound exploration, the structural damage is assessed and a plan is made for determining the involvement of specific synovial structures which could number as high as 4: the coffin joint, the pastern joint, the digital flexor tendon sheath, and the navicular bursa.

|

|

Figure 7. Lavage of a tendon sheath under general anesthesia which communicated with a severely traumatized and contaminated heel bulb laceration. Notice the tourniquet at the left edge of the picture. This was used for the simultaneous IV regional limb perfusion which delivered super high concentrations of antibiotic to the wound while the wound was being lavaged and debrided. |

All of the involved structures need to be lavaged in order to clear any contamination before infection sets in. This lavage can either be performed standing or under anesthesia and using either arthroscopy or multiple needles inserted into the joint, depending on the details of the situation.

Following lavage, antibiotics may be administered either directly into the joint or as an intravenous regional limb perfusion. Both of these techniques achieve extremely high concentrations of antibiotics in the area of the wound. Devitalized tissues are then removed from the wound. Ideally the wound is then sutured closed as with wounds in other locations. However, wound closure may be delayed in some wounds that are highly infected or contaminated.

|

Figure 9. Appearance of a fresh heel bulb laceration that has been closed and is ready for a foot cast. |

Figure 10. Appearance of a foot cast just after application for a heel bulb laceration. The horse will stay in this cast for 2-3 weeks until removal. |

Finally, the issue of hoof movement needs to be addressed. This depends on the wound configuration. Some heel bulb lacerations can be treated successfully with simple bandaging and stall confinement. Most, however, require the use of a foot cast in order to adequately stabilize the wound. This can seem daunting to many owners but in reality, most wounds that require a cast heal faster, heal with a more cosmetic appearance, result in a reduced workload on the owner, and potentially have a lower final cost to the treatment when compared with bandaging or leaving the wound open. Many times, especially with a fresh clean wound, the cast can be applied immediately and the horse treated on an outpatient basis. Other times, casting may be delayed in heavily traumatized, contaminated, or infected wounds to allow further treatment of these complicated cases. After casting, horses will need stall confinement for 2-3 weeks before the cast is removed. Following cast removal additional bandaging or special shoeing may be needed to fully address the damage from the wound.

Fortunately, the prognosis for horses to return to their intended use following heel bulb lacerations is good. Roughly, 80-90% of horses can be expected to fully recover without complications and return to work provided that vital structures aren’t severely damaged or a severe joint infection doesn’t develop. As for Rocket and Emma’s case…..Luckily no synovial structures were injured and the wound healed well without the need for a foot cast. Rocket is currently teaching my niece how to run the barrels.

The Heat and Your Horse

Katie Delph, DVM, MS, DACVIM

With this seemingly never-ending heat wave, it is important to consider heat safety in not only our small animal pets but also our equine friends. Horses, unlike small animals and other large animals, can sweat, and evaporative heat loss is one of the primary ways horses cool down when environmental temperatures are high. Heat production in the horse’s body comes from skeletal muscle activity and deep internal organs like the gastrointestinal tract digesting food. During exercise, skeletal muscle activity can generate enormous amounts of heat that may overwhelm the body’s capabilities to dissipate it.

When both the temperature and humidity are high, the horse’s ability to dissipate heat through the evaporation of sweat becomes significantly compromised. Other ways horses dissipate body heat are through conduction or convection. Conduction is the transfer of heat by directly contacting a cooler object. Convection occurs through air movement where warmed air overlying skin is replaced by cooler air through wind currents to cool the skin. When horses are enclosed in a poorly-ventilated area (like a horse trailer, for example), the warmed air overlying the skin is not replaced by cooler air resulting in inability to dissipate heat through convection. You may also notice that when you exercise your horse at higher speeds, your horse does not appear to be hot; but when you slow down to a walk or stop, he heats up. This is because of the greater air currents resulting in more convection during higher speeds, and lower or lack of air currents resulting in less convection during low speeds.

The danger with your horse not being able to dissipate heat properly is if they overheat and become exhausted or heat stressed. As the horse’s body temperature reaches critically high levels, the horse quickly becomes dehydrated and has metabolic derangements that may be followed by organ failure, seizures, collapse, and even death.

Treatment for heat stress includes moving the horse to an area with shade and high air flow. Repeat cool water baths while scraping off warmed water with a sweat scraper. If the water is not scraped off, it quickly heats up and can actually act to insulate the body. Ice water baths or ice strategically placed over the jugular veins and in the inguinal areas (if safe) can help to cool blood flow to internal organs. Offer cool water to drink or your veterinarian may pass a nasogastric tube to administer cool water. In severe cases, intravenous fluid supplementation may be needed to cool the patient as well as treat significant dehydration.

Clinical signs to watch for that could mean your horse is in danger of heat stress include:

- Increased respiratory rate, nostril flare, panting

- Increased body temperature (over 102.5 degrees F)

- Depression

- Reduced performance and fatigue

- Weakness

- Profuse sweating or lack of appropriate sweating

- Prolonged skin tent or dry, pale mucous membranes

- Elevated heart rate

- Even more severe signs include cold extremities, seizures, and even death

Ways to prevent heat stress in your horse include:

- Ensuring shade is available

- Constant availability of fresh, clean, cool water

- Provide electrolytes or salt block to encourage water intake

- Providing fans in common areas to increase air flow, ventilation, and effectiveness of convection

- Preemptively cool water bathe and scrape your horse on hot days

- Allow a period of adaptation to heat especially if moving from a cooler to warmer climate

- Only exercise your horse during cooler parts of the day in shade if available

- Ensure your horse is fit for exercise prior to hot summer months

- Allow plenty of breaks during exercise for your horse to dissipate body heat

- Clip heavily-haired horses in the summer

If you notice that your horse is not sweating like you would expect them to, they may be suffering from an inability to sweat or anhidrosis. If this is the case, you should contact your veterinarian or the KSU-VHC as your horse will need even more help staying cool. If you are concerned about heat stress in your horse, contact your veterinarian or the Kansas State University Veterinary Health Center immediately as you are taking steps to try to cool your horse.