Blister Beetles in Alfalfa

Blister Beetles in Alfalfa

What is lurking in the alfalfa? Blister Beetle Poisoning in Horses

Amanda Trimble, DVM, Equine Internal Medicine Resident

|

|

Figure 1: Striped blister beetle |

|

|

|

Figure 2: Horses that suffer from blister beetle toxicity have a tendency to submerge their muzzle in water in an effort to soothe irritated oral tissues. Note this horse is |

|

A. B. |

|

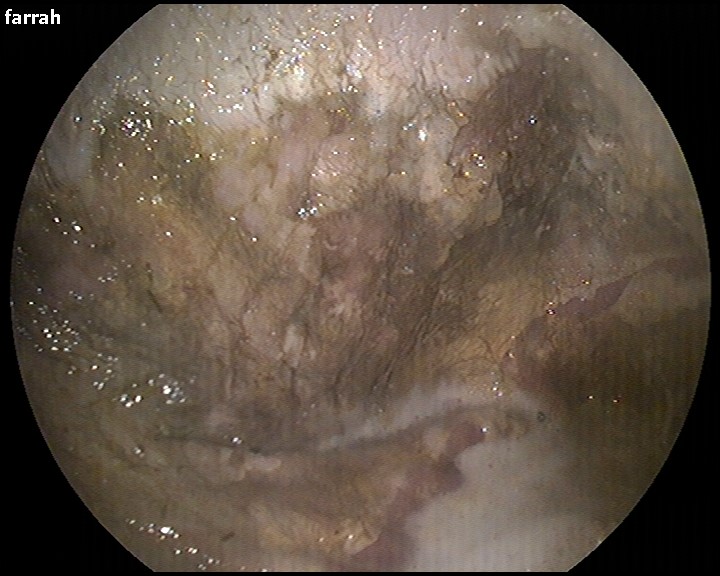

Figure 3: gastric ulceration is a common development following ingestion of blister beetles. A) demonstrates a healthy stomach the upper light colored area and lower pink areas are normal components of the gastric lining in horses, whereas B) reveals the changes that can be seen in association with cantharidin toxicity. The horse in panel B has loss of the normal light colored (squamous) area which has suffered from extensive ulceration. |

Kansas and Oklahoma are unique with regard to having an ideal climate for the cultivation of blister beetles, which can cause devastating disease in horses. This article is aimed at increasing the awareness of horse owners and individuals that may purchase alfalfa hay that has been grown in this geographic region. Additionally, this information will help horse owners recognize clinical signs and use feeding strategies aimed at prevention of potential toxicity.

What is blister beetle poisoning?

Blister beetles are small insects that live in alfalfa hay (Figure 1). They contain a toxin, called cantharidin, which causes ulceration of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and urinary system in horses when it is inadvertently ingested. Cantharidin can cause topical skin irritation people who come in contact with beetles.

Severity of poisoning in horses is dependent on how much cantharidin is ingested.

What signs should I look for in my horse?

Horses with blister beetle poisoning can present with a variety of clinical signs, usually within 3-18 hours of ingesting the toxin. The most common presenting sign is colic. Horses may have a fever (T> 101.5 F), diarrhea, have a decreased appetite, or seem depressed and lethargic. The first sign in horses may be a horse dunking its whole face into the water bucket or aggressive playing with its water bucket (Figure 2). Oral ulcers are very painful, and water dunking is believed to be a pain relieving strategy adopted by affected horses. Frequent urination may also be a common presenting sign. Blood may be present in the urine, but often cannot be seen by simple visual inspection.

In horses that experience clinical signs of toxicity, severe gastric ulceration and electrolyte abnormalities may occur (Figure 3). Blood testing can determine a very low calcium concentration which can cause a condition known as “thumps” also called synchronous diaphragmatic flutter (SDF). Synchronous diaphragmatic flutter occurs when electrolyte levels are at a dangerously low concentration, most commonly associated with low calcium levels.

The low electrolyte concentrations interfere with normal nerve condition which leads to simultaneous heart and respiratory rates. It may appear that your horse is having hiccups. However, if left untreated, this condition can be fatal.

Can my horse be treated?

The good news is that in most cases, yes! It ultimately comes down to how much cantharidin your horse ingested and how quickly treatment is implemented. Treatment goals include removing toxin that may still be present in the stomach and provision of aggressive supportive care. A toxin adsorbant, such as activated charcoal or Biosponge® may be given via nasogastric intubation. Intravenous fluids containing calcium are commonly required to correct electrolyte abnormalities and dehydration, and to protect the kidneys from further damage. Due to the severe gastric ulceration that occurs with toxin exposure, a course of Gastrogard® (Omeprazole) which facilitates gastric ulcer healing and sucralfate which coats the ulcerated mucosa are prescribed. An easy to digest diet consisting of warm mashes is commonly offered until complete recovery from toxin ingestion, in general a week to 10 days.

How is cantharidin toxicity diagnosed?

Typically, clinical signs are very indicative of this disease. Veterinarians can test urine or gastric contents for the presence of cantharidin.

How can I prevent this toxicity?

Blister beetles live in alfalfa hay, so if you do not feed alfalfa, you have a much lower risk of your horses being exposed. If you do feed alfalfa, avoid feeding later cuttings of alfalfa hay. Usually first cutting alfalfa is the safest to feed, because the beetles have not yet clustered in the fields.

There is a direct seasonal relationship with season and beetle swarms on pasture. As the weather warms the beetles are more prevalent on pastures. The first cutting is generally considered safest based on the cooler temperatures.

Other strategies that limit the likelihood of beetle exposure include alfalfa that is harvested at < 20% bloom and the avoidance of using a crimper during the baling process. The crimper is more likely to trap beetles during harvest.

If you notice any of the above signs, promptly contact your veterinarian!

- Discontinue alfalfa feeding to all other horses.

- Contact your veterinarian for examination of the potentially affected horses.

- Have the alfalfa inspected to see if there are any beetles present.